How Minnesota codes can prepare our homes and spaces for resilience, utility, and affordability.

A critical transition is underway in Minnesota that will have a resounding impact on the future of our built environment: The state of Minnesota is accelerating the efficiency in our residential and commercial energy codes, requiring all new residential and commercial construction to be nearly passive to heat and cool by 2038. In other words, an energy fortress. This is a commitment to the comfort, air quality, efficiency, and climate readiness of our buildings.

Before scrolling away because this topic seems too boring or technical, look around—chances are, you’re in a building right now. Americans spend roughly 90 percent of their time in buildings, which are also responsible for a whopping 40 percent of U.S. greenhouse gas emissions.

Constructing a building is the first and often best chance to determine how much energy it will consume. Building codes (which you will be an expert in a few short minutes) set the floor on what we can expect from a newly constructed building. This is why building codes are too important to take for granted, especially because residents and local leaders have the power to make a significant impact strengthening the climate- and human-impact of our buildings via the code adoption process. In this post, we will demystify this process and show you how to contribute to the conversation.

To start, most of us already know a few basics about building codes. For example, if you’re selling a house, you likely know that you can’t count basement rooms as bedrooms if they don’t have egress or escape windows. Why is that? Our residential building code requires that basement bedrooms must have escape windows. Or you might be fond of lamenting to friends and family that aspects of your old house are not “up to code,” for example when you find yourself shivering next to a wall with no insulation, or when plugging in a space heater involves a 34-step process to make sure that it doesn’t trip the breaker.

Building codes establish the minimum standards for a building’s quality, safety, energy use, and construction. Constructing a building “to code” means that the building will meet the minimum state requirements, but only that. Building developers and owners can always construct buildings that are more efficient than the code requires, but never less efficient. This is why establishing strong building codes are a critical policy to improve energy efficiency, reduce carbon emissions, and speed the transition to a clean energy economy for everyone.

What are building codes?

Modern building codes are highly technical, but in a way, the basic concept has been around for thousands of years. In the 1700s B.C., The Code of Hammurabi stated that “If a builder builds a house for someone, and does not construct it properly, and the house which he built fall in and kill its owner, then that builder shall be put to death.”

Today, codes are less punitive and more detailed. The Minnesota State Building Code contains 20 chapters covering everything from efficiency and accessibility to fire protection, electrical, and plumbing.

How many bathrooms does a theater need? It’s in the building code.

How thick does the fireplace hearth need to be? There’s a code for that (minimum four inches).

Don’t understand an acronym in the code? There’s an entire section of referenced standards, where you might learn (if you didn’t already know!) that AMCA stands for the Air Movement and Control Association International, which has standardized “Laboratory Methods of Testing Air Curtain Units for Aerodynamic Performance Rating,” a term which has (somehow) not yet been made into this acronym: LMOTACUFAPR. I guess everyone has their limit?

So, who writes these incredibly detailed codes? In most cases, the first draft of the code is a generic, “model” code created by an organization like the International Code Council (ICC) or the National Fire Protection Association (NFPA). These standards developing organizations convene committees of relevant industries, advocates, non-profits, and state and local code enforcement officials to update new versions of their model code books every three years. Then in Minnesota, the Department of Labor and Industry (DLI) amends the model code with any state-specific changes before adopting it.

Like many areas of regulation, the Minnesota Legislature plays a limited role in managing building code updates, instead granting authority to a state agency (DLI, in this case) to administer the code adoption and modification process. The state law regarding building codes addresses three main purposes: 1) the authority of DLI to update and enforce codes, 2) the purpose of building code compliance and enforcement, and 3) where the code is and is not used. While some states allow cities to adopt stricter codes than the statewide standard (called stretch codes), Minnesota law currently prohibits local governments from adopting anything other than the State Building Code.

Does the Building Code apply to all buildings in Minnesota? Not quite. All new commercial, residential, and government buildings must comply with the Minnesota Building Code (though state buildings are also held to their own higher standards as well). However, existing buildings are not required to meet today’s building code unless the owners make renovations. If an owner or contractor seeks proper approval from their local code enforcement office, they will have to bring the specific elements they’re updating up to code. However, this is a narrow requirement—an electrical update in one room will not necessarily require electrical updates in the next room—much less require updates to unrelated aspects such as plumbing.

There are other exceptions as well, including some agricultural buildings and manufactured homes—which are governed by the national Manufactured Home Construction and Safety Standards, administered by the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development.

Is the Energy Code different from the Building Code?

We’ve talked a lot so far about building codes, but where does energy fit in? The Energy Code simply refers to two chapters in the Minnesota Building Code: Chapter 1322, Residential Energy Code, and Chapter 1323, Commercial Energy Code.

What’s actually in this energy code?

Because almost everything about a building affects how energy is used, the energy code covers many elements, including requirements for the building’s:

- Envelope—in other words, everything that separates the outdoors from the indoors. Think about air leakage around doors, window quality, and insulation requirements for outside walls.

- Heating and cooling systems, including requirements for ducts, thermostats, system efficiency, and more. This is where HVAC fits in, which stands for Heating, Ventilation, and Air Conditioning.

- Water heaters and hot water pipe insulation.

- Electrical wiring and lighting systems.

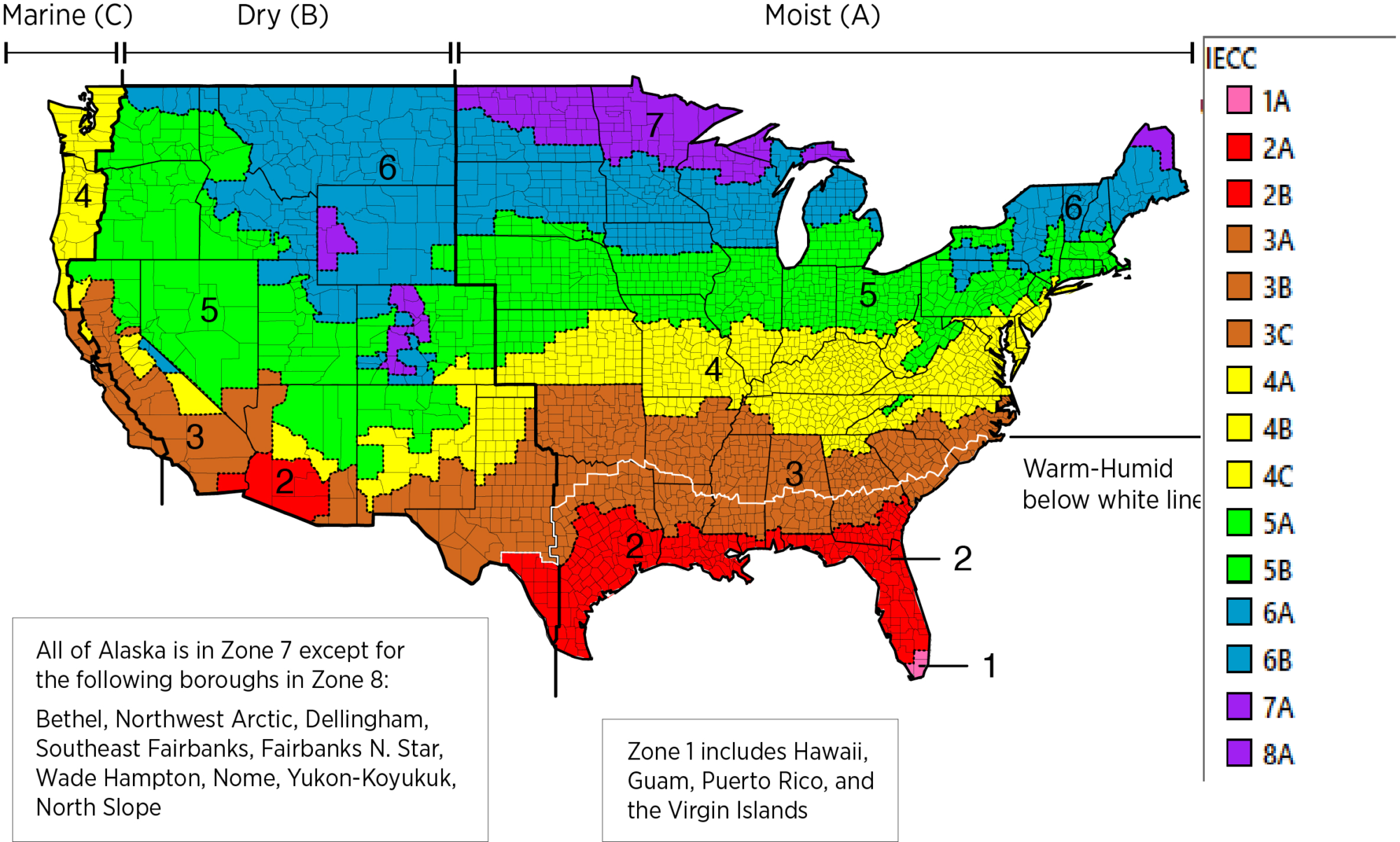

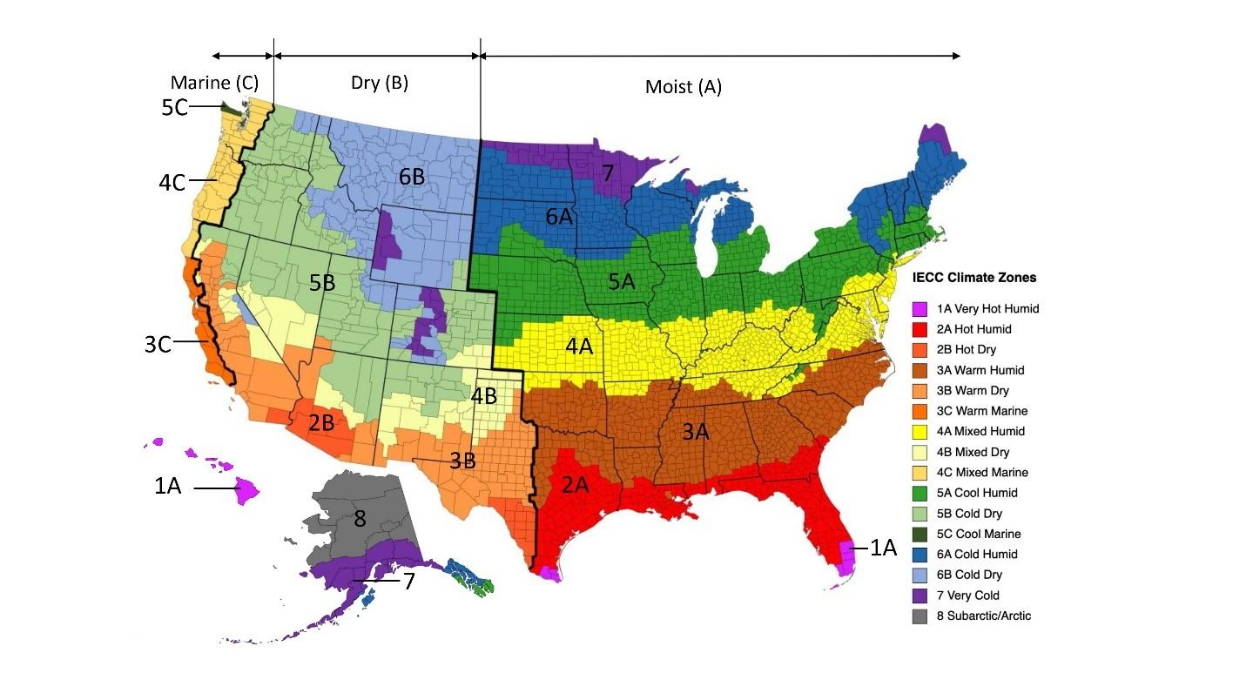

These specifications also change depending on location. Energy code requirements vary by climate zone, generally becoming stricter the farther north, you move in the United States (this is most notable for envelope and HVAC requirements—lighting doesn’t change from one zone to another). For now, Minnesota has two climate zones: Southern Minnesota is in Zone 6, and Northern Minnesota is in Zone 7. However, as climate change moves these zones north, this will eventually change. In fact, the ICC already classifies a few Southern Minnesota counties as Climate Zone 5—but these will remain Zone 6 in the next Minnesota code update for consistency.

Comparing the ICC Climate Zones from their 2018 and 2021 model codes provides a fairly sobering reminder that climate change is already here and happening:

IECC Climate Codes

2003 – 2018

2021

There are two model energy codes used by most jurisdictions in the United States: The International Energy Conservation Code (IECC), which is written by the ICC, and ASHRAE-90.1: Energy Standard for Buildings Except Low-Rise Residential Buildings, which is written by ASHRAE, the American Society of Heating, Refrigerating and Air-Conditioning Engineers. Every three years, ASHRAE publishes an updated model energy code. Two years later, and on their own three-year cycle, the ICC releases an updated IECC, which is based in part on the latest ASHRAE 90.1 standard.

Currently, Minnesota uses an amended version of the 2012 IECC for residential buildings and an amended version of ASHRAE 90.1-2019 for commercial buildings.

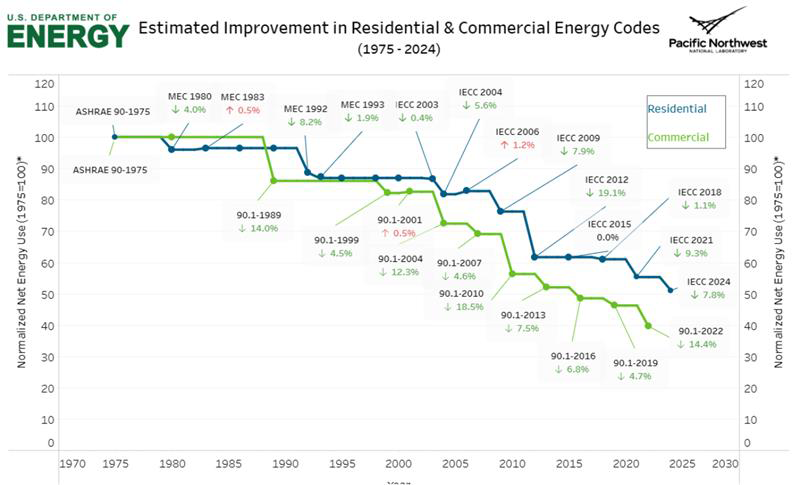

One of the simplest predictors of a code’s energy efficiency is the year it was published. For example, ASHRAE 90.1-2019 is more efficient than ASHRAE 90.1-2001 and the 2018 IECC is more efficient than the 2009 IECC. In the figure below, you can see how each iteration of energy codes generally improves upon its predecessor, visualized by decreasing energy use on the graph.

The U.S. Department of Energy’s Building Energy Codes Program tracks the estimated efficiency improvements in buildings following the model energy code over time. View this and other energy code infographics here.

Multiplied across the state, the financial and carbon emission savings from the ever-improving energy code are significant. Pacific Northwest National Laboratory (PNNL) estimated that adopting the residential components of the 2021 IECC in Minnesota would save consumers an average $231 in the first year of adoption. The same report estimated carbon reductions of 9,524,000 metric tons over 30 years, “equivalent to the annual CO2 emissions of 2,071,000 cars on the road.” This doesn’t even include the estimated jobs created, increased quality of life from better buildings, or grid benefits from much lower peak demand.

How are building energy codes used?

While codes benefit every resident, user, and owner of a building, there are three main stakeholder groups that need to know the detailed requirements of the energy code:

- manufacturers;

- architects, builders, and contractors; and

- code enforcement officials.

First, manufacturers of building materials use the model energy codes to create products that will meet minimum standard requirements across the country. For example, insulation is rated by R-value, which is the “resistance” to heat transfer through the material. Code regulates the minimum R-values for insulation across the building, and requires that the R-value be displayed on insulation products. To ensure compliance, manufacturers produce insulation that will provide the necessary “thermal resistance,” and ensure that the rating is printed across the product for visibility.

Second, architects, builders, and contractors use products from those manufacturers to design and construct buildings that, at a minimum, meet the code. Not only do builders need to purchase and combine the right set of building materials, they also have to assemble and install them correctly. If all the insulation has the right R-value but is installed with large gaps, the builder hasn’t followed code.

To provide flexibility to architects and builders, energy codes provide multiple compliance pathways to choose from: prescriptive or performance-based. These compliance pathways are included in the model codes adopted by states across the country, so industry professionals are generally familiar with the options.

The prescriptive path provides a longer but more straightforward checklist. As long as the builder uses the appropriate R-values and other minimum standard products, follows appropriate construction techniques, and achieves minimum air tightness, the code official will approve the project.

| Example prescriptive requirements |

|---|

| Residential buildings in Minnesota must have ceiling/attic borders insulated to R-49 or more. (TABLE R402.1.1) The same goes for commercial buildings (TABLE C402.1.3 OPAQUE THERMAL ENVELOPE INSULATION COMPONENT MINIMUM REQUIREMENTS, R-VALUE METHOD a, i) |

| Regarding air barriers and insulation. “Ceiling/attic: Access openings, drop down stair or knee wall doors to unconditioned attic spaces shall be sealed.” (TABLE R402.4.1.1 AIR BARRIER AND INSULATION INSTALLATION) |

| “The building or dwelling unit shall be tested and verified as having an air leakage rate of not exceeding 5 air changes per hour in Climate Zones 1 and 2, and 3 air changes per hour in Climate Zones 3 through 8” (R402.4.1.2 Testing.) |

| As an alternative to insulating floors over crawl spaces, crawl space walls shall be permitted to be insulated when the crawl space is not vented to the outside. (R402.2.10 Crawl space walls.) |

A performance path allows more wiggle room on specifics and allows a designer to use a computer model that demonstrates that the overall project meets basic efficiency requirements. This approach could allow, for example, a wall or window that doesn’t meet prescriptive requirements for insulation or air sealing. But if the building team knows they can make up that efficiency in other parts of the building, the performance approach will give them this flexibility.

Finally, local code enforcement officials complete the process by inspecting plans, issuing permits, and conducting inspections on new buildings and major renovations. You can find your local building code officials on the Minnesota State Building Code Jurisdiction Directory. The enforcement of codes could be its own blog post, but suffice it to say that code enforcement is a very important part of the codes discussion.

How are building energy codes updated?

Codes and their update processes vary from state to state. While the federal government requires states to consider updates to their state energy code based on new model codes (consider, but not necessarily adopt). Some states, like North Dakota, do not have a mandatory state-wide energy code. Some states allow local governments to adopt “stretch codes” that set higher standards in the city or county than in the rest of the state.

Minnesota has a uniform statewide building code, which cannot be amended by local governments. In other words, no stretch codes here.

Using the latest ASHRAE-90.1 for Commercial and International Energy Conservation Code for Residential, Minnesota updates energy codes every 3 years. Other Minnesota Building Codes are updated on a 6 year cycle.

With input from the public and experts, DLI staff revise model code language to include Minnesota-specific changes, and then publish the updated State Building Codes. Staff work closely with appointed members of the Construction Codes Advisory Council (CCAC). While the CCAC reviews all code language before final adoption, they appoint subcommittees of technical advisors, called Technical Advisory Groups (TAGs), to do the line-by-line review and edits of a specific model code.

Anyone from the public can access current and recent TAG information here, review notes and future agendas, and find information to follow along remotely, or attend a meeting in person in St. Paul. Anyone with the knowledge and interest can also participate in the process by drafting a Code Change Proposal (CCP), raising a hand to speak in a meeting, volunteering to be a member of a TAG, or all of the above! Want to really get into the weeds? The Residential Energy Code TAG page has a list of all the CCPs submitted so far: click here for some light weekend reading about U-values, fenestrations, and ERI scores.

Bookending the Technical Advisory Groups, CCAC review, and a few other steps, there are hearings with an administrative law judge, where we also participate to protect and advance efficiency and resilience.

In 2020, DLI considered and declined to adopt the residential provisions of the 2018 IECC. Our residential energy code is currently a weakened version of the 2012 code, which means that a lot of energy savings have been left on the table since then, but also that a lot of emissions reductions are possible if we update. Currently, DLI is preparing to adopt the 2024 IECC as the basis of our residential energy code, which would dramatically increase the efficiency and resilience of all new residential buildings in Minnesota.

Modernizing our building code will also bring us in line with other states who are leading on climate and energy issues. The U.S. Department of Energy’s Building Energy Codes Program tracks state level energy code adoption and is a great place to learn more about residential and commercial energy codes across the country.

While Minnesota has made notable commitments to clean energy and climate policy, until recently, our building code has represented an under-used policy tool to improve our resilience, health, safety, comfort, utility costs, and emissions across the state.

In 2023 and 2024, that changed with bold new legislative requirements for the Commercial and Residential energy codes, which will require “near zero” new construction by 2036 (Commercial) and 2038 (Residential). To keep on track, the energy code acceleration laws also require energy code updates every 3 years instead of every 6. Specifically the law now requires:

- 80% less energy use in the 2036 Commercial Energy Code, compared to a 2004 baseline

- 70% less energy use in the 2038 Residential Energy Code, compared to a 2006 baseline

This is a huge victory for everyone hoping to lower emissions from the building sector, more savings on utilities, and maximum comfort in even the most extreme temperatures.

What’s next for energy codes in Minnesota?

Fresh Energy is taking action on multiple levels to improve building codes for health, savings, and climate.

First, we are participating in the state’s Commercial and Residential Energy Code TAGs and the Residential Building Code TAG. Together with our partners, Fresh Energy has prepared comments, testimony, and a coalition to voice strong support for 1) adopting the latest energy codes, 2) advocating against amendments that weaken the efficiency of the code and cut into critical energy savings potential, and 3) supporting amendments that strengthen the efficiency and emissions reductions of the model code.

Second, we continue to advocate with state legislators for better codes, better buildings policies, and the investments we need to build and retrofit the climate smart homes and other buildings of the future.

Phew. I know that was a lot of information. But give yourself a pat on the back for learning a bit about building and energy codes and why they are such an important tool to address climate change. And stay tuned for future buildings-related pieces from your friends at Fresh Energy.