A former U.S. president’s clean energy legacy is supporting pollinators and stormwater management in his hometown of Plains, Georgia.

Developer: SolAmerica Energy

Location: Plains, Georgia (Sumter County)

Size: 1.3 megawatts

Soil type: Sandy clay

Annual precipitation: 49 inches

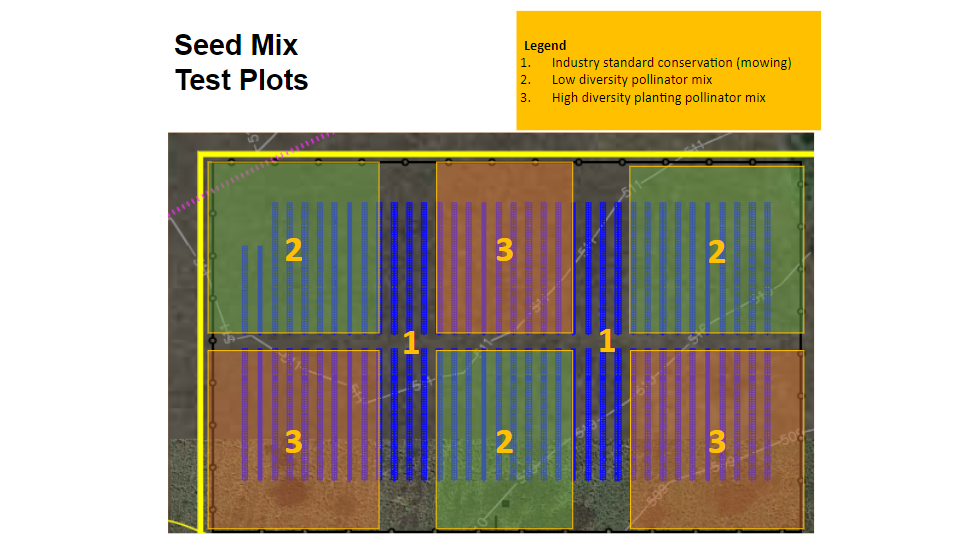

Ground cover: Three different seed mixes, including the industry-standard grass, a low-diversity pollinator mix, and a high-diversity planting pollinator mix.

Funded by the U.S. Department of Energy’s (DOE) Solar Energy Technology Office, the Photovoltaic Stormwater Management Research and Testing (PV-SMaRT) project from Great Plains Institute, DOE’s National Renewable Energy Laboratory, Fresh Energy, and the University of Minnesota is using five existing ground-mounted photovoltaic (PV) solar sites across the United States to study stormwater infiltration and runoff at solar farms. Together, the five sites represent a range of elevations, slopes, soil types, and geographical locations that will help solar developers and owners, utility companies, communities, and clean energy and climate advocates better understand how best to support solar projects and the host communities in which they are built, in particular lowering the costs of clean energy development while ensuring protection of the host community’s surface and ground waters.

Site background

Former President Jimmy Carter was an early advocate for clean energy development across the United States, from the West Wing of the White House to pockets of rural America, like his hometown of Plains, Georgia. Today, seven acres of a 25-acre parcel of former President Carter’s land, where peanuts and soybeans used to grow, is now home to a solar farm that can power more than half of Plains, a city of around 640 people. Situated in the middle of what is now a neighborhood, the project began when solar developer SolAmerica Energy approached the former President’s family about the possibility of installing panels on the land. That solar site now feeds into Georgia Power’s grid and is helping restore pollinator habitat, a well-known priority for former First Lady Rosalynn Carter, who helped create the Rosalynn Carter Butterfly Trail.

A flat site with sandy clay soil, Carter Farms hosts 3,852 solar panels to provide 1.3 megawatts of electricity to the Plains community via tracking, one-in-portrait arrays. Across six plots, the site is also testing three separate seed mixes to monitor how the various ground cover intersects with stormwater management:

- Crabgrass, annual ryegrass, and panicum

- Low-diversity pollinator mix (7 species): Indian blanketflower, common sensitive plant, butterfly milkweed, southern elephant’s foot, finged bluestar, rayless sunflower, southern beardtongue

- High-diversity pollinator mix (18 species): Indian blanketflower, partridge pea, blackeyed Susan, yarrow, lanceleaf coreopsis, southern elephant’s foot, mistflower, and others

Since the site was first built to accommodate the solar industry standard of planting some sort of grass underneath the panels, which requires more frequent mowing, the PV-SMaRT team and local partners are still monitoring the six different plots to determine the full impact of the pollinator-friendly seed mixes at the Carter Farms site.

Bodie Pennisi, a professor of horticulture with the University of Georgia, reports that, so far, the dominant grasses in the control areas have been crabgrass, annual ryegrass, and panicum. “2022 is the year when we expect the strongest bloom from the perennial species, and we are really excited to see what pollinators and other beneficial insects come to the flowers.”

Although the site plots are still being monitored, that hasn’t stopped researchers and other project participants from drawing initial conclusions and getting excited about the many benefits the pollinator mixes will bring for biodiversity, the climate, and SolAmerica’s site management costs.

Research process

As discussed in our first PV-SMaRT case study on Connexus Energy’s Minnesota site, when engineers and researchers sit down to plan out or conduct analyses on clean energy developments like solar farms, they often utilize something called a design storm to test how well the site will hold up against an extreme weather event like a flood. A design storm is essentially a test flood event of a certain magnitude—the higher the magnitude, the more intense the test storm for modelling and analysis purposes. These tests help researchers and engineers monitor rainfall and soil moisture as well as determine how fast excess water soaks into the ground during extreme storms.

Jake Galzki, a University of Minnesota researcher who is part of the modeling team for the PV-SMaRT project, says, “The Carter Farms site has a deeper profile than other sites we’ve studied – it’s a meter and a half to the nearest restrictive layer. That means the rooting depth for ground cover is deeper than other sites. And the soil at this site is essentially a 1:1 sandy clay, meaning it is comprised of 50 percent clay and 50 percent sand.” He adds, “In terms of measuring the runoff at Carter Farms against the other four project sites, the runoff here is moderate despite being the wettest site we’ve studied. We noted good infiltration capacity when testing the 100-year design storm, but we also did see some runoff due to the high clay content of the soil, which is very typical during such extreme events.”

Aaron Hanson, energy program specialist at the University of Minnesota’s Institute on the Environment, says: “It’s great that we have such diversity among our research sites. The climate and soil conditions in southern Georgia are quite different from what we are used to in Minnesota. The ‘growing season’ is actually reversed. Rather than having snow cover in the winter, they have a dormant period during the heat of the summer. This diversity of research site conditions will ultimately help our model to be applicable for solar developments across the country.”

Craig Kvien, one member of a small crew of folks managing the site down in Plains, is an agricultural specialist whose expertise with innovative solar and agricultural projects runs decades deep. Craig says that the process for tending to the plots has of course come with its challenges, namely weeds. “We’ve got a team of people who’ve been sampling and documenting the plant and insect species that are out there over time, including the ones we anticipated, and those we did not,” Craig says with a chuckle. He adds, “Part of the process for ensuring the pollinator mixes can thrive requires a good amount of effort to beat down the weeds that also want to grow.”

But Craig isn’t daunted by what he calls a “standard mix of hard-to-get-rid-of weeds, which includes briars.” When asked what it is about the project that excites him the most, he doesn’t hesitate to remark on the beauty of a multi-use property: “There are lots of options. It seems silly not to do something useful with the land underneath the solar panels, particularly if you can make a difference somehow, either by enhancing the pollinator species in the area—or making or saving an extra buck.”

Project site and benefits

“This site in Georgia helps bring both scientific validity to the modeling and runoff coefficients, adding diversity of soil types, hydrology, and land use,” said Brian Ross, vice president and project lead at the Great Plains Institute, “but also to develop regulatory, permitting, and project best practices that flow from the science. Georgia regulators have been participating in these discussions and helping ensure that the science is ultimately reflected in the practice.”

John Buffington, vice president of SolAmerica Energy, says the pollinator piece was a key consideration for the company. “SolAmerica was originally motivated by the opportunity to contribute to the restoration of pollinator habitats,” John says. “We think supporting these initiatives is the right thing to do and gives us an opportunity to be a more engaged member of the communities in which our solar developments are located. Later, we were excited to hear about the stormwater and cost management aspects of pollinator-friendly solar.”

According to John and the SolAmerica team, pollinator-friendly solar has the potential to change the whole solar industry. “We could have done a pollinator project and just been quiet about it,” he admits. “But that wasn’t the intent, because we were trying to inspire the industry, and the Carter site was a great vehicle for that. These pollinator-friendly and stormwater supporting practices help contribute to better management of a site by reducing the amount of our budget that goes to mowing and other maintenance. So, beyond the pollinator restoration aspect, there are clear business benefits to doing this with a solar site.”

Stakeholder feedback

Like the other PV-SMaRT sites, data and observations from the Carter Farms site now serve as a benchmark as the PV-SMaRT research team continues to gather insight about each of the five project sites across the country. Overall, ongoing findings at the Carter Farms site further validate the project’s recommended best practices for solar developments and stormwater management: We can help lower the soft cost of clean energy development and of ongoing maintenance, protect the host community’s surface and ground waters, create needed habitat, and sequester carbon in the soil all while helping craft a truly sustainable clean energy future that will benefit everyone for generations to come—just as the Carters have long worked towards.

Throughout 2022, experts and stakeholders will be reconvening in this process to continue to examine and provide feedback on this foundational research. Read the first PV-SMaRT case study on Connexus Energy’s Minnesota site, get the latest updates from Great Plains Institute, and stay tuned for the third and final PV-SMaRT case study from Fresh Energy and partners soon!